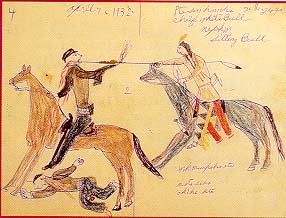

White Bull obtains a first coup as he lances and unhorses

a U.S. Indian scout near Pumpkin Buttes in Wyoming, August, 1865.

Theirs was a culture that had been

made possible by horses, enabling them to abandon a sedentary life based

on agriculture and roam freely over a great expanse. Warriors were constantly

on the alert for opportunities to steal horses from enemy tribesmen like

the Crows and Pawnees, or from the whites, who began to invade Sioux territory

in the 1840s.

In a society that was dependent on the fighting abilities of its men,

it is not strange that Sioux developed a social system that gave first position

to the bravest warriors, and evolved a coup system to measure courage. There

usually were three grades of coups, ranked in the order in which warriors

managed to touch an armed and dangerous foe. The object in striking coup

was to demonstrate one's bravery by getting that close to a formidable foe,

rather than standing off at relatively safe distance and dispatching him

with a rifle or bow.

The warrior who claimed to have struck a coup had to have witnesses willing

to substantiate his claim. Having achieved this recognition, the warrior

was encouraged to recite the circumstances of the coup before gatherings

of his people.

Whether raiding for houses or trading blows with the enemy, the Sioux

emphasis was on the individual. Horses he captured |

did not become band property, rather, they were the warrior's

to dispose of as he chose. Likewise, fighting was not a true team effort,

but an opportunity for the individual to demonstrate courage and gain coups.

By the time he was in his mid-twenties, White Bull had over thirty of the

coveted awards and enjoyed the highest status the Sioux accorded the brave.

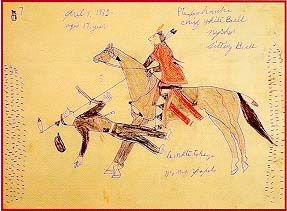

White Bull depicts himself lancing a soldier during the

Fetterman Fight near Ft. Kearney, Wyoming, December 1866. Two bullet holes

can be seen in White Bull's cape.

White Bull's celebration of his

achievements was not confined to the recitation of his coups at appropriate

times. Depicting the specific action that merited the coup on a tepee cover

or a buffalo robe was common by the mid-nineteenth century. The logical

next step when paper became available was to use this convenient medium

to record the coups. Ledgers discarded by or seized from the U.S. Army or trading

stores began to make their way into the hands of warrior-artists.

According to students of ledger art, it began to die out in the 1890s

as Sioux males confined to reservations no longer were able to earn the

coups to record. White Bull retained, however, the pictographic record that

he had compiled soon after entering the reservation.

At first glance, pictographs seemed to be a simple two-dimensional art.

But if one comprehends the conventions (see next page) |